At the last auction of the 364-day Treasury Bills on June 1, the cut-off yield crossed 6 per cent to reach 6.0801 per cent. The last time we saw the cut-off yield of this instrument exceed 6 per cent was on July 10, 2019 (6.0611 per cent).

What was the level of retail inflation then? In July 2019, the consumer price index (CPI)-based inflation was 3.15 per cent, down from 3.18 per cent in June. What was the policy repo rate? It was on a downward trajectory – 5.75 per cent, from 6 per cent in April, with two more rate cuts following.

After the latest off-cycle rate hike, the repo rate is now 4.4 per cent. The CPI inflation in April was 7.79 per cent, and no one is expecting a dramatic drop in May. Retail inflation may hover around 7 per cent in the next few months before shooting up again to well above 7 per cent in August and inching close to 8 per cent in September. This is despite a series of steps taken by the government, including a cut in excise duty on petrol and diesel.

Only a sudden collapse in global commodity and domestic food prices can change the scenario.

Does this mean that we may see a massive rate hike on June 8 when the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) rate-setting body, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), ends its three-day meeting?

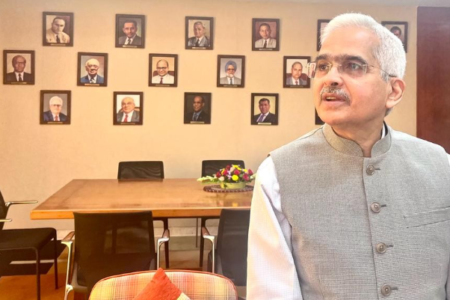

In the RBI governor’s words, a rate hike in June is a “no brainer”. At the same time, he has been continuously stressing on a “calibrated” approach as the governor doesn’t believe in the dictum: “The operation was successful but the patient is dead.”

So, the June rate hike is unlikely to be 1 percentage point or even 75 basis points to take the repo rate to the pre-pandemic level of 5.15 per cent. One basis point is a hundredth of a percentage point.

On October 4, 2019, the repo rate was cut from 5.40 per cent to 5.15 per cent. Months later, in the last week of March 2020, when the Covid pandemic hit India, it was cut to 4.4 per cent; another rate cut followed in May to bring it down to a historic low of 4 per cent. Both were off-cycle rate cuts.

My guess is the MPC will lift the repo rate to the pre-pandemic level of 5.15 per cent in two phases over June and August. To reach there, we need a 75 bps rate hike, which could be split into two – 50 and 25 bps or 40 and 35 bps – over the next two meetings. This week we are likely to see a 50 or 40 bps repo rate hike to take it to 4.8 or 4.9 per cent. Correspondingly, the rate of standing deposit facility (SDF), which has replaced reverse repo, will rise, keeping a gap of 25 basis points between the two rates.

Commercial banks borrow money from the RBI at the repo rate and park their money with the central bank when they have excess liquidity at the SDF rate.

The 5.15 per cent pre-Covid repo rate will not signal the end of the rate hike cycle. It is likely to continue with a pause after August or September (the October MPC meeting has been advanced to September-end). The overnight index swap (OIS) rates, a measure of market expectations on the money market rates, are pricing in 7.25 per cent repo rate by June 2023.

Will the MPC go to that extent? Certainly not since the RBI can’t throw growth out of the window even as taming inflation is its priority at the moment. But one can expect the repo rate to rise to at least 6 per cent by April 2023, if not earlier.

Retail inflation surged to 7.79 per cent in May, the highest since May 2014. With this, retail inflation has been above the upper limit of the central bank’s flexible inflation target band (4 per cent +/- 2 per cent) for four months in a row. Most analysts expect it to remain above the upper end of the band till February 2023 before it falls below 6 per cent in March 2023.

If retail inflation overshoots the upper band of the target for three successive quarters, the RBI needs to explain the reasons to the government. It did happen in 2020 but no explanation was required from the regulator as April and May inflation figures were not considered for the breach because of difficulties in data collection when a lockdown was in place to fight the Covid pandemic. This time, it seems, there won’t be any escape for the central bank.

In February, it had estimated just 4.5 per cent average inflation for FY23. The Russia-Ukraine war and its impact on the oil price, among other things, forced it to raise the estimate to 5.7 per cent in April. We will see another upward revision this week. The analyst community expects average inflation for FY23 to be around 6.5 per cent.

The forecast for growth was also cut by 60 bps to 7.2 per cent in April. Even though every multilateral and rating agency has been revising India’s growth estimate downward, the RBI might not be in a hurry to pare it again next week.

The repo rate was brought down to its historic low of 4 per cent in May 2020 but the real effective policy rate was far lower – 3.35 per cent reverse repo rate. The RBI cut it from 3.75 per cent to 3.35 per cent on May 22, 2020 outside the MPC meeting. Since there was too much money in the system, the banks kept their excess liquidity with the RBI, making reverse repo the policy rate.

The RBI did introduce variable reverse repo rate auctions first (in January 2021) to lift the short-term rates and finally brought in SDF in April, killing the reverse repo instrument. In the current liquidity framework, repo is also not the primary instrument to infuse liquidity. Banks are required to knock at the marginal standing facility, or MSF, window to access short- term money at 25 bps higher than repo rate — 4.65 per cent now.

Along with the hike in repo rate as well as SDF, will we see another hike in banks’ cash reserve ratio (CRR)? It’s the portion of deposits that banks are required to keep with the RBI on which they don’t earn any interest. In May, along with the repo rate hike, CRR was also raised by 50 bps, sucking out Rs87,000 crore from the system. We may not see another round of CRR hike as the average liquidity in the system is far lower now than it was even a few months back – almost half of it.

The latest RBI Report on Currency and Finance has indicated that any surplus liquidity over 1.52 per cent of banks’ net demand and time liability (NDTL), a loose proxy for deposits, is inflationary. Until recently, it was double of this; and, at its peak, liquidity was three times or even more. Now, it is hovering around 2 per cent of NDTL. It may shrink further if the RBI needs to buy dollars to stem the erosion in the value of the local currency as for every dollar it buys, an equivalent amount of the rupee is sucked out of the system.

An offshoot of the drop in excess liquidity is the repo rate once again becoming the policy rate, which was not the case when there was liquidity sugar rush.

An interesting thing to watch out for in this week’s policy is its language and forward guidance. While the statement is expected to continue to harp on the withdrawal of accommodation, will it continue to talk about a “multi-year” timeframe for doing so? Also, will it nuance its approach to liquidity? Isn’t it the time to talk about “appropriate” liquidity instead of “adequate” liquidity, dear Governor?