The Indian economy expanded 7.6 per cent in the September quarter of financial year 2024, beating analysts’ estimates by a wide margin and confirming the narrative that indeed India is the fastest-growing major economy in the world. It’s also 110 basis points (bps) higher than the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) projection of the second quarter gross domestic product (GDP) growth. One bp is a hundredth of a percentage point.

Against this backdrop, what will the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), the Indian central bank’s rate-setting body that will hold its bimonthly meeting this week, do? Before I get into the guessing game, let’s look at the other relevant data — what has changed since the last MPC meeting that ended on October 6?

Retail inflation softened to its four-month low of 4.87 per cent year-on-year in October, from 5.02 per cent in September, driven by a broad-based decline in the so-called core or non-food, non-oil inflation as well as fuel inflation while food inflation did not show any sign of decline. Its peak during the current financial year has been 7.44 per cent (in July 2023). Core inflation inched down to around 4.2 per cent in October from around 4.5 per cent in September.

The Brent crude price, which had been $83.8 a gallon on October 6, dropped to $79.00 on December 1. In the past two months, since the last policy, the crude price fluctuated between $76.6 and $93.79.

Growth in the index of industrial production (IIP) faltered in September to 5.8 per cent after a rise in the previous two months. Still, the IIP growth in the second quarter of FY24 has been stronger at 7.4 per cent versus 4.8 per cent in the first half.

There hasn’t been much change in the yield of 10-year government bonds either. From 7.34 per cent on October 6, it’s down to 7.29 per cent over the weekend, after veering between 7.19 per cent and 7.4 per cent in the past two months. In contrast, the yield of the US 10-year paper has slid from 4.74 per cent on October 6 to 4.20 per cent on December 1, widening the spread between Indian and US paper yields.

There hasn’t been much change in the level of the rupee vis-à-vis the dollar during this time. On October 6, a dollar had fetched Rs83.22; last week it closed at 83.30, a day after an all-time closing low for the local currency (83.3938). In the same period, the dollar index — a measure of the US dollar’s value relative to the majority of its most significant trading partners — softened a bit, from 106.04 to 103.4. (This is where the RBI may be more cautious as despite a lower dollar index the rupee is trading near its weakest level.)

Among other parameters to watch out for, the liquidity deficit in the system, which touched Rs2.24 trillion one day in the third week of November, the highest since December 2021, has been modest at both points — Rs34,000 crore on October 6 and Rs49,000 crore on December 1.

Let’s take a look at what other major central banks have done in the past two months.

In the last week of October, the European Central Bank (ECB) left its policy rate unchanged at a record high of 4 per cent after raising it at 10 consecutive meetings from July 2022. With inflation in the eurozone declining to 2.4 per cent in November, down from 2.9 per cent in October, the 2 per cent inflation target is back in ECB’s focus for the first time since 2021 summer. Lower inflation could signal an imminent shift in the stance of the monetary policy.

In November, the Federal Open Market Committee, the rate-setting body of the US Federal Reserve, unanimously decided to keep the benchmark rate unchanged at 5.25-5.5 per cent for the second time in a row amid hopes that the Fed will no longer raise the policy rate and may start cutting it by springtime.

Last month, the MPC of Bank of England (BoE), too, kept the rate unchanged at 5.25 per cent but the decision was not unanimous — three of the nine members preferred another 25-bps hike. BoE Governor Andrew Bailey has made it clear that despite the fall in inflation, “there is absolutely no room for complacency” and even if further tightening is not needed, “it is much too early to be thinking about rate cuts”.

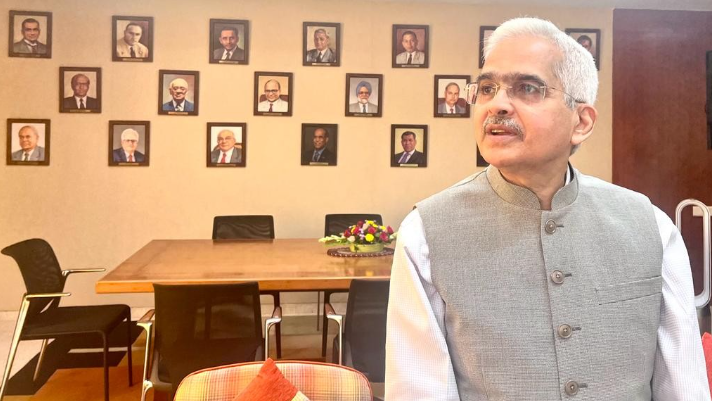

In Bailey’s talk, don’t you hear an echo of what RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das had said after the October policy announcement? This time, too, there will be a status quo — no change in the policy rate as well as the stance. And in his statement, Das will be as cautious — if not hawkish (like October) — as he has been since the April policy.

In October, the repo remained unchanged at 6.5 per cent — for eight months in a row after being raised by 250 bps between May 2022 and February 2023. The policy stance was also unchanged — withdrawal of accommodation. There was no change in the inflation as well growth estimate for the year either.

The RBI in October announced plans to sell government bonds through open market operation (OMO) for managing liquidity (read tightening), in sync with the stance of the policy. But it has not happened yet. There have been instances of the RBI selling bonds through screen-based trading in the secondary market, even before the October policy and after that, but no sale has happened through auctions as liquidity has been tight, largely because of the government’s huge surplus that may change post-state elections as spending gathers speed.

The main focus of the last policy meeting was on liquidity, which had swelled following the return of the Rs2,000 currency notes to the banking system. The RBI will not take its eyes off the liquidity management even though we may not see OMO auctions.

Driven by higher food prices, retail inflation will rise in November (blame it on onion and potato) before slightly dropping in December, but low core inflation is an assurance that the policy is working well.

There is unlikely to be any change in the retail inflation estimate for FY24 — 5.4 per cent. Will there be any change in the GDP growth projection for the year? There could be. The RBI may raise it from 6.5 per cent to 6.7-6.8 per cent or leave it as it is with an upside bias, instead of with risks “evenly balanced” to have the victory lap later.

With major global central banks pressing the pause button, inflation easing globally and US bond yield dropping, the pressure is off but don’t expect any action from the RBI. It will remain vigilant and resolutely focused on aligning inflation to the 4 per cent target on a durable basis.

When will we see the first rate cut? Let’s wait for the change in stance first. And, also, the rate cut by the US Federal Reserve. The earliest it can happen is in June next year, provided the script remains positive on geopolitics, inflation, growth and the global interest rate trajectory.

This column first appeared in Business Standard.

The writer, a Senior Adviser to Jana Small Finance Bank, writes Banker’s Trust every Monday in Business Standard.

Latest book Roller Coaster: An Affair with Banking

Twitter: TamalBandyo

Website: https://bankerstrust.in