The World Gold Council (WGC), in partnership with India Post and Reliance Money Infrastructure Ltd, is celebrating this festive season by offering customers a 7% special discount on gold coins sold from post offices across India. Between 16 October and 31 December, customers can purchase 99.9% pure, Swiss-made 24-carat gold coins in denominations ranging from half a gram to 50g from 1,120 outlets.

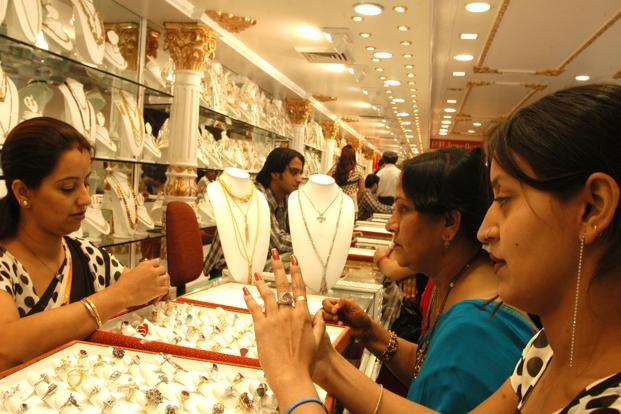

Both Dussehra and Dhanteras are considered auspicious days to buy gold. So is Akshaya Tritiya. This April, on Akshaya Tritiya, Indian consumers’ lust for the yellow metal pushed up sales 10-15% despite a spurt in prices. Going by the All India Gems and Jewellery Trade Federation’s data, gold sales averaged between 40 tonnes and 42 tonnes in the past three years on Akshaya Tritiya, after a record 55 tonnes in 2008. At Rs.28,885 per 10g, gold was up 32.4% on that day in Mumbai from Rs.21,815 last Akshaya Tritiya.

While jewellery sales have been going down, gold coin purchases are on the rise. According to WGC data, gold jewellery sales dropped 14% in 2011, but the sale of bars and coins grew 5% last year. In terms of consumer demand, India ranks first in the world—roughly accounting for a quarter of the global demand—closely followed by China. And among Indian states, per-capita gold consumption is the highest in Kerala.

India’s gold imports—about 1,067 tonnes for some $60 billion (around Rs.3 trillion today), next only to oil and more than what we spend on importing fertilizer—were responsible for the 30-year record high current account deficit in fiscal 2012, 4.2% of gross domestic product. In 2011, gold imports were to the tune of $40 billion. Experts attribute the increase of $20 billion to high inflation as people typically buy gold as a hedge against inflation.

Gold demand in India was down in the first three months of fiscal 2013 and in the full year, but nobody is sure whether this trend will continue. In 2011, India imported 933.4 tonnes of gold, and in 2010, some 1,006 tonnes. Compare this with gold demand of about 400 tonnes a year in the early 1990s and about 65 tonnes in the early 1980s.

Gold imports have been down due to a number of factors such as the new tax on gold jewellery, increases in the import duty for gold, and a depreciating rupee till mid-September. In the February budget, the government raised the import duty on non-standard gold to 10% from 5% to slow down the rising imports that bring down the widening current account deficit. On gold coins and platinum, duty was raised to 4% from 2%.

Bharatiya Janata Party president Nitin Gadkari last week suggested India should auction its public sector gold mines to raise domestic gold production through state-of-the-art technology and reduce dependence on imports. Mining and production of gold in India is minimal—in 1995, it was around 2 tonnes against the world production of 2,272 tonnes; the scenario hasn’t changed drastically since then.

Till restrictions were lifted on gold imports and a few commercial banks were allowed to import gold and sell the yellow metal to jewellers and exporters in 1997, the spread between the London and Mumbai market prices was huge, but that has shrunk dramatically. There is no incentive for gold smuggling any more, but with the bank and post office branches selling gold coins to retail customers, we are facing a different problem—a wider current account deficit. Historically, the government and the Reserve Bank of India have tried hard to wean away people from gold and bring the yellow metal out of household closets for productive purpose without any success. In November 1962, a 6.5%, 15-year gold bond was floated, but it could collect only 16.7 tonnes. Subsequently, in March 1965, a 7% ,1980 gold bond could mobilize 6.1 tonnes, and the third bond, floated in October 1965, mobilized 13.7 tonnes. Yet another gold bond scheme of 1993 mopped up 41 tonnes, and a gold deposit scheme, introduced by banks in 1997, didn’t elicit much response.

In the April-June quarter of the current fiscal, India’s current account deficit was down to $16.55 billion from $21.76 billion in the January-March quarter. The moderation was due to a sharp decline in imports compared with exports; the drop in oil and gold prices as well as a 18.4% contraction in gold imports year-on-year helped. But the trend may reverse if inflation and inflation expectations continue to remain high. In September, wholesale price inflation rose to a ten-month high of 7.81%, higher than what analysts had expected.

It’s not easy to wean away consumers from buying gold when it is freely available because of the cultural factor. On top of that, most other assets have been offering negative or no return. The post-tax, inflation-adjusted return from bank deposits has been negative in the past few years. India’s bellwether equity index, the Sensex, has risen about 20% since January after losing close to 25% in 2011, but the retail investors have rarely made money in the equity market. So, the only asset they are investing in is gold (and real estate for wealthy individuals). Bank branches and post office outlets are only whetting their insatiable appetite.

While inflation needs to be contained, the authorities need to take a relook at the gold sale policy and the drain on foreign exchange as the yellow metal has no productive use. Gold loan schemes of some of the banks and non-banking finance companies have been doing well, but they have been able to bring out a small portion of gold hoarding out in the open. The collective obsession of 1.2 billion people with gold can play havoc in the economy unless the government and the central bank draw up a plan to tackle it.