T he person who did this act on the Indian banking system and others who may be planning further such acts are evil people. They don’t represent business community; they don’t represent a legitimate group of promoters. They are flat bank defaulters. The only thing they can think about is default. As a nation of good folks, we are going to hunt them down; and we are going to find them, and we will bring them to justice.

The search is underway for those who are behind these defaults—the rogue promoters as well as the bankers who facilitate the loans that go bad. We will direct the full resources of our intelligence and law enforcement communities to find those responsible and bring them to justice. We will make no distinction between the promoters who committed these acts and those who facilitate them.

God bless India.

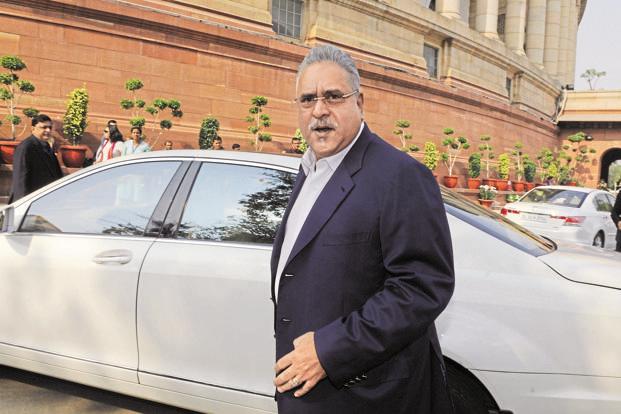

Given a choice, the Indian government, politicians of different hues as well as a part of the media would have loved to address the nation this way after UB Group chairman Vijay Mallya, whose grounded Kingfisher Airlines Ltd has not returned some Rs.9,100 crore to a consortium of banks led by State Bank of India, left for the UK on 2 March.

I will not be surprised if Mallya says he is afraid of coming back to India as he runs the risk of being lynched by a mob. Bankers, too, are scurrying for cover as everybody is questioning their expertise and integrity.

I don’t have great admiration for Mallya. Only once I came close to saying hello to him at his Mumbai office but the meeting, arranged by his communication executive, never took place. I left after waiting for close to two hours. I cannot comment on other allegations against Mallya, but punctuality has certainly never been his virtue.

While none can question the efforts of getting Mallya back to India and recovering the money from him since he had offered a personal guarantee to the banks when the loan was restructured, the collective rhetoric against defaulters and public sector bankers could end up killing the industry as well as the banks. As we are tarring everybody with the same brush, it is blurring the distinction between the bad and the ugly among the borrowers and fast diminishing bankers’ appetite for risk.

The multibillion-dollar Eurotunnel, the undersea rail link between Britain and France, has been a nightmare for lenders because of cost overruns that forced massive debt restructuring in 2007. Globally, business failures and commercial decisions going wrong are a reality, but can we criminalize business failures? If we do so, banks will stop lending to the industry and the government’s efforts to push up the contribution of manufacturing to India’s economy from the current level will limp.

Venture capital can support the start-ups, but we need bank loans if big projects are to take off. Indeed, we can shift the focus and decide to become an agrarian economy, but even that won’t solve the problem as farm loan waivers will always remain a threat to the banking system’s health and credit culture.

So, what’s the way forward?

In developed markets, the banking system typically meets the need of the retail borrowers while the corporate bond market takes care of the money that large industrial houses require and the creation of infrastructure is the responsibility of the government. In India, the banks are expected to do all.

Till the late 1990s, banks had mostly focussed on giving working capital loans. Sensing an opportunity, they got into retail financing early this century even as the death of the development finance institutions such as the Industrial Credit and Investment Corp. of India (ICICI) and Industrial Development Bank of India pushed the banks into project financing. They love displaying the tag of a universal bank which can do everything under the sun, but the bankers never developed the skill for appraisal of projects and monitoring them.

Project appraisals

For project appraisals, they typically depend on chartered accountants, external valuers, the so-called lenders’ engineers or the agency involved in technical due diligence and risk assessment of projects and investment banks such as SBI Capital Markets. Since the investment banks are appointed by the borrowers, they often end up selling many not-so-credit-worthy projects to the banking community.

Since the public sector banks neither can develop project appraisal skills overnight nor can they pay top dollars to attract talent from the market, it’s time they set up a project appraisal agency for doing this job. In 1987, ICICI, Unit Trust of India and a few other financial institutions had set up India’s first credit rating agency, Crisil Ltd. Almost three decades later, a similar structure can be replicated for a different purpose.

State Bank of India (SBI), the nation’s largest lender, can take the lead and a few others can chip in with equities and set up such an agency. It must be run by competent professionals who understand the risks and rewards of giving money to different sectors. The bankers should have nothing to do with such an institution, barring setting this up and outsourcing project appraisals to it.

Indeed, external developments such as delays in getting regulatory clearances will lead to time and cost overruns and jeopardize the viability of certain projects, but to some extent, such an agency will put a lid on the fresh creation of bad loans. However, what should be done with the stock of bad assets?

For the listed banks, the rise in bad assets has been close to a trillion in the December quarter—from Rs.3.4 trillion to Rs.4.38 trillion. After provisions, net non-performing assets or NPAs of the banking industry in the December quarter crossed Rs.2.5 trillion and the state-run banks account for more than 90% of this. According to a Reserve Bank of India estimate, in the September quarter, the combination of recognized NPAs, restructured assets as well as written-off assets was to the tune of 17% for public sector banks and 14.1% for the industry. I bet both will rise further in the March quarter as banks continue their clean-up drive, goaded by the regulator.

Over the past fortnight, finance minister Arun Jaitley has reiterated that the banks must endeavour to get back every single penny lent to corporate houses. In a rare advisory last Friday, the government—the majority owner of the public sector banks—instructed the lenders to start invoking personal guarantees of promoters and recover the dues without losing time in case companies have failed to repay the loans. An eminent lawyer himself, I am sure Jaitley is well aware of the legal framework within which the banks operate.

Legal hurdles

There were some 72,500 pending cases in the debt recovery tribunals or DRTs in December 2015 involving close to Rs.4 trillion, little less than the heap of bad assets of listed banks at that time. A quasi-judicial forum to facilitate debt recovery by banks, a DRT is expected to dispose of a case that banks refer to it within 180 days, but each of the 33 DRTs operating in India are struggling with 2,200 pending cases on average every year.

The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (Sarfaesi) Act, a 2002 law, empowers banks to attach assets of defaulters, but it is easier said than done as the DRTs are not equipped to handle so many cases even as the defaulters move from such tribunals to high courts and even the Supreme Court to buy time.

In the Mallya case, the banks had moved the DRTs in 2012. There have been at least 20 cases pending and hundreds of hearings and adjournments at different DRTs, high courts and the Supreme Court. The efforts to recover money have been on for four years, but everybody has woken up now, after Mallya left the country.

And, here is how the cases referred to the DRTs swelled in the past five years in tandem with the rise in banks’ bad debt. In 2011, the tribunals disposed of 12,122 cases involving Rs.21,155 crore, but there were 54,061 cases pending and the amount involved was to the tune of Rs.1.46 trillion. In 2012, the number of pending cases dropped to 41,205 and the amount involved to Rs.1.31 trillion, but in 2013, the number of cases rose to 47,933 and the money involved increased to Rs.1.79 trillion. In 2014, there were 59,645 cases involving Rs.3.75 trillion. Going by its past record, even if the banks do not move the tribunals with a single fresh case, it will take at least six years to clear the pending cases.

The proposed bankruptcy code will not be able to change the scenario overnight. It is too aggressive even by the standards of developed markets and it will not be easy to implement unless the government puts in place the right logistics.

Recapitalize and privatize

Everybody seems to be agitated on bank recapitalization and rightly so. After all, why should the government continue to use taxpayers’ money to keep the public sector banks alive? Including the Rs.25,000 crore bank recapitalization announced in the recent budget, the government will end up spending close to Rs.93,000 crore in the six years since 2010 to keep these banks running. Higher NPAs also prevent banks from paying a higher interest rate to the depositors and lower loan rate to the borrowers as they struggle to set aside money to provide for bad loans and that erodes their profitability.

The best solution is, of course, privatization. Instead of pushing for consolidation, the government should decide to bring its stake in public sector banks to below 50% and stop sending advisories to them. The chances of getting its money back from privately run banks is far more than public banks as they will continue to make the same mistakes and need more money in future.

After the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in September 2008, the US Treasury announced a Troubled Asset Relief Program or TARP of up to $700 billion to save its privately managed banks being submerged in the so-called subprime mortgage crisis. Till 14 March, $619 billion has been invested, loaned or paid out by the Treasury even as the banks have returned $683 billion in the form of interest, dividend and fees. The Treasury has earned some $64.5 billion or more than 10% return on its investment. The Indian government cannot expect such returns from its fund infusion in the public sector banks unless they are privatized.

Since this will not happen anytime soon as the government does not have the stomach to take such a politically sensitive decision, it must address issues such as strengthening the legal system, bank boards and building expertise by offering right incentives on a war footing. An aggressive fishing expedition on every defaulter and banks may do more harm than good to the economy unless India has many Walt Disneys who have unique business ideas and can fund their own projects.