Globally, bankers are broadly expected to do three things: collect deposits, give loans, and invest in government bonds and other financial instruments. In India, they end up doing a few other things as well, including picking up a broom and cleaning up neighbourhoods where bank branches are located as part of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Mission). Ironically, balance sheets of many banks in India at the moment are in dire need of a clean-up.

In 2015, the Indian banking community took a break from other activities. It was busy opening deposits under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, a national mission to promote financial inclusion. The result is there for everyone to see. Banks have so far opened 307.6 million accounts under the drive launched in August 2014. Government-owned banks have opened more than 90% of the accounts. At this point, the beneficiaries are keeping Rs71,232.93 crore in these accounts.

The next year tells a different story. In 2016, bankers were busy counting notes, literally. In 50 days in November and December, Rs15.4 trillion worth of currency notes in Rs1,000 and Rs500 denominations—some 86.9% of the value of total banknotes in circulation—were withdrawn after a historic address to the nation by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. One of the many objectives of this black swan event was to attack hoarders of black money, or unaccounted, untaxed wealth.

It was the responsibility of bankers to check the colour of money at over 116,000 bank branches and stack new currency notes in 208,000 automated teller machines (ATMs) across the country.

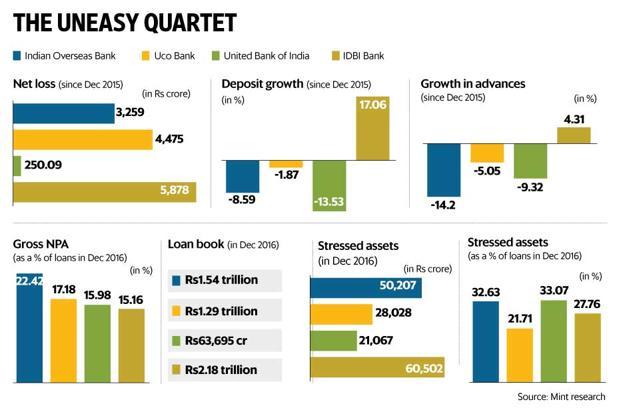

In 2017, bankers spent their time and energy in taking loan defaulters to court. Weighed down by Rs10 trillion of stressed assets, they have been chasing rogue borrowers; but in 2017, it became a mission, pushed by an aggressive banking regulator. Armed with an ordinance which gave it powers to direct banks to chase defaulters, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in June identified 12 loan accounts with 25% share of gross bad loans in the system for immediate bankruptcy proceedings. At that time, the central bank said lenders should finalize a resolution plan within six months for their top 500 stressed accounts; if they failed to find a resolution through other means, they should move court to declare defaulters bankrupt.

Fast losing patience, in August, RBI followed it up with another list of 28 large stressed accounts and asked banks to either resolve them by December or start insolvency proceedings. These 28 accounts collectively have exposure of Rs1.4 trillion. Going by media reports, bankers have not been able to resolve most of the cases and they are being referred to the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) for bankruptcy proceedings.

What will be the dominant banking trend in 2018?

One thing is for sure. Along with fighting pitched battles with loan defaulters, bankers will start giving loans anew. For the past three years, credit growth, particularly for the public sector banks, has been tepid.

Some public sector banks have even shrunk their loan books. A weak investment climate has been responsible for this. Over-leveraged Indian companies have had neither the capability nor the inclination to lift bank credit and set up new projects. This is expected to change in 2018.

Better cash flows, higher capacity utilization and a pick-up in some high-frequency indicators are encouraging analysts to anticipate an upturn in private capital expenditure—if not across sectors, at least in some select pockets.

Banks, too, have been reluctant to lend in recent years for fear of piling up more bad assets. Banks do not earn any interest on bad loans; on top of that, they need to set aside money to cover the risk of default on such loans. This hits profitability. Hefty provisions have also pushed many banks into losses and eroded their capital. This is why they have been diffident about lending.

The government has addressed this by announcing a big bang Rs2.11 trillion recapitalization of state-owned banks. This is some 1.3% of India’s GDP. While a debate is under way on whether this will be enough to meet the capital needs of public sector banks (keeping in mind the needs under Basel III norms, which will be in place in 2019) and how much of this fund infusion is growth capital, one thing is certain: there will be strings attached to the disbursement of this money. RBI and the finance ministry have been jointly working on this.

Recapitalization is not something new for India’s state-owned banks. In the past 31 years, between 1985-86 and 2016-17, the government had infused much less, some Rs1.51 trillion in the state-owned banks.

Historically, the finance ministry, representing the government, the majority owner of this group of banks, decides on which bank gets how much capital. It has been a sort of democratic exercise where banks get funds according to their size and not their efficiency and prospects. For the first time, they would need to earn this money.

There will be definite preconditions and only when they accept those conditions will the banks get a lifeline in the shape of recapitalization bonds.

In other words, bank recapitalization and banking reforms will go hand in hand.

It may be too early to expect dramatic mergers and consolidation among public sector banks, but we will definitely see some banks aggressively selling non-core assets and shrinking their balance sheets.

Finally, if early indications are anything to go by, 2018 could be the first year of bad loan resolution. When a series of restructuring exercises packaged by the banking regulator failed, RBI inspectors took upon themselves the job of identifying bad loans and forcing banks to clean up balance sheets under the so-called asset quality review (AQR) in 2015. In the scheme of things, the banks were to come clean by March 2017 but like a magician’s inexhaustible bottle of water, many Indian banks’ balance sheets keep exposing new bad loans.

Until 2017, the focus had been on recognition of bad loans clogging the system. Resolution and recovery are expected to start in 2018.