For a moment, let’s presume the Indian government has signed off the privatization plan of national carrier Air India. Four investment bankers chosen for the deal have done a fantastic job in finding out the right suitor. Like most public sector mandates, they have done it free for prestige, moving up the league table and brushing shoulders with the government (not necessarily in this order). After the celebrations get over, all four get notices from India’s tax authorities, asking them to pay goods and services tax, or GST, on their fees that never were.

Well, they may not have earned any fees but a notional fee that they would have got in the normal course—a percentage of the deal size—could easily be calculated and tax needs to be paid on that. After all, they have provided a service, which is taxable. It’s another matter that there is no “consideration” for the service, and it’s a “contract” between the investment bankers and the government.

Or, say, you decide to open a restaurant. You start charging your customer on every dish and liquor served but breadbasket and pickle are complimentary. One fine morning, you get a notice from the tax authorities, saying they don’t care whether you are charging or not for the crispy whole wheat bread sticks that people savour with tomato soup. Many of your patrons actually love that and, apart from good food and service, that’s also a reason why they come to your restaurant. So, you assign (impute, in tax parlance) a value of the breadbasket and pickle served and pay tax on them.

Still, if you are not getting it, take the instance of a large Indian corporation that has shaken India’s digital ecosystem, offering telecom and internet services dirt cheap, or even free, at the initial stage. How will it react if it gets a notice from tax authorities to pay tax on the free services that it has offered to woo customers?

A New Challenge

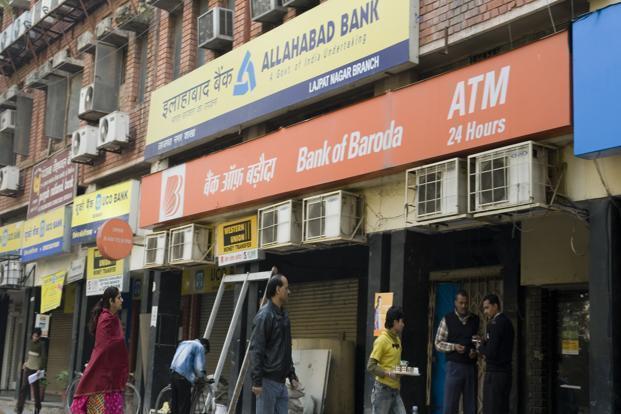

Reeling under a pile of bad loans that is getting larger every three months and rising bond yields that have been eroding the value of its investment portfolio, the Rs120 trillion Indian banking industry is facing a new challenge—this time from the government, the majority owner of 70% of the industry. The Directorate General of Goods and Services Tax Intelligence (DGGSTI), part of the department of revenue, ministry of finance, has served show-cause notices to banks, asking them to explain why penalty and interest will not be charged on the service tax they had not paid for five years—between July 2012 and June 2017—till GST came into being.

The services in question are those that banks offer free—such as a certain number of cash withdrawals from ATMs, money transfer through net banking, cheque books and the quarterly statement of accounts, debit cards, refund of fuel surcharge, among others—to customers if a minimum balance is kept in deposits.

The quantum of minimum balance varies from bank to bank. If a customer does not keep the minimum balance, she is either charged a penalty, or each of the services offered is charged. Banks have been paying tax on these (penalties and fees), but they have not paid service tax on the services offered free in lieu of minimum balance kept in accounts. Many banks have received notices, following an investigation by tax authorities; for others, such notices are on their way. A back-of-the-envelope calculation by a large consulting firm puts the tax burden for the entire industry at around Rs45,000 crore. If we add interest and penalty, it could be as much as Rs1.35 trillion. The amount could rise even further as tax authorities may explore the possibility of covering the period from July 2017, too, when GST was introduced and service tax ceased to exist. (The relevant authorities have been kept in the loop on the show-cause notices served.)

Why Five-Year Tax Arrears?

Why has the demand been for the past five years and not, say, 10 years, or even 23 years, since 1994, when service tax was introduced? There could be two reasons. One, DGGSTI has found out a way to establish that free banking services are covered within the definition of “declared services”, a concept introduced in July 2012, and, two, under the erstwhile service tax law (governed by the Finance Act, 1994), the maximum period for re-opening old matters (where tax authorities believe service tax has not been paid or paid but not fully because of fraud or collusion or wilful mis-statement or suppression of facts) is five years.

Even though it started in 1994, the scope of service tax got extended periodically till 2012, when a negative list was introduced once and for all, making it clear that all the services not featured in the list are taxable. The negative list includes services offered by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), trading of goods, selling of space for advertisements in print media, transmission or distribution of electricity by a utility and certain banking services such as interest on loans and deposits and buy and sale of foreign currency among banks.

What Is Service?

Finally, how do we define a service? Under the erstwhile service tax law, any activity carried out by a person for another for a consideration is service, but it specifically excluded certain activities such as transfer of goods or immovable property, services rendered by employees to employers, a transaction in money (depositing money in a bank account or withdrawal of money) and an “actionable claim”—a loose proxy for unsecured debt.

The GST law has changed the definition. Now, services are anything other than goods, money and securities. However, they include activities relating to the use of money or currency conversion by cash or any other mode for which a separate consideration is charged.

Consideration Vs Contract

Essentially, “consideration”, or fees being paid for a service, is key to the service tax computation. In private, most bank chief executive officers are calling the government claim “imaginary” and “bizarre” as there was no consideration involved. They have been offering the services free as part of a contract (between banks and their customers). So, why should they pay service tax?

Tax authorities, however, have a different point of view. According to them, a bank commits to offer the services/facilities free in lieu of a “recurrent commitment from the customer” for maintaining a minimum balance in her account. The bank is “rendering an activity… to the customer. It is also a case of … agreeing to the obligation to do an act”. The customer’s understanding represents consideration of the bank—it is a non-monetary consideration. Moreover, maintaining minimum balance is akin to a maintenance fee.

The banks have been offering the services to their customers for a consideration other than price—the ability to earn by deploying the funds or through commissions on investments made from the funds through the banks. Since this is a non-monetary consideration that the banks are earning, it should be valued under a prescribed mechanism as per the service tax rules of 2006. The penalty that the banks levy on customers for non-maintenance of minimum balance gives us an idea of how to value the free services.

In sum, the tax authorities’ arguments are:

# There is an agreement for an activity;

# There is consideration;

# The consideration is in non-monetary terms;

# The monetary value of the consideration is determinable.

The banking community is not convinced, as in taxation and criminality, the written law should be in force, and not the unwritten “spirit” of the law, they say. Under the service tax law, it is clear that only services rendered for a consideration should be taxable and even if we assume there is a consideration for these services, it is defined to be “zero” as per contractual arrangements (between banks and customers). Simply put, in the absence of a legal provision, one cannot impute the value of a service that is being offered free.

Incidentally, valuation rules under the GST regime are more explicit to convey this intent of the law. Section 7 of the CGST Act (read with Schedule 1) clearly suggests services without consideration supplied to related persons/affiliate entities only qualify as “supply of services”. Accordingly, services without consideration provided to unrelated parties should not constitute “supply” and, hence, not taxable.

The GST valuation rules also say where the supply of goods or services is for a consideration not wholly in money, the value of the supply is determined by its open market value. If the open market value is not available, there are other ways of computing the value. I am refraining from getting into those details, which are too technical. Those interested can check (https://bit.ly/2rpQ4Ez).

I understand the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), the national bankers’ lobby, is in the process of appointing one of the Big Four accounting firms to represent the industry’s case to the government. It is also discussing the way forward with a large law firm.

Indeed, the government is exploring every possible way to raise tax collection. For the first time, GST collection crossed Rs1 trillion in April, riding on economic recovery as well as improvement in tax compliance. A higher tax collection helps shrink the fiscal deficit and ensure capital expenditure by the government. So, what is the way forward?

The Way Forward

If IBA can convince the government, the tax authorities may refrain from pursuing the case. If that does not happen, the bankers’ body may move the court, citing lack of clarity in the service tax norms on assigning value for free services. Also, in the absence of clarity, it cannot be imposed with retrospective effect, could be IBA’s line of argument. (Finance minister Arun Jaitley’s stance on any retrospective decision on tax matters is well known.)

Typically, it takes long to resolve such cases. I am tempted to refer to the case of rounding-off interest tax by banks. Between October 1991 and March 2000, there was a 3% tax on interest charged on borrowers (meaning, if one was paying 10% on a loan, the actual cost of the loan would have been 10.3%). When banks started rounding off the tax (instead of 10.3%, 10.5% in this case), a public interest litigation (PIL) was filed before the Karnataka high court, describing such rounding-off as illegal. The high court, convinced in the merit of the PIL, held that action of rounding-off as illegal, arbitrary and untenable, and asked banks to deposit the money collected with RBI. The Supreme Court, too, affirmed the decision of the high court and said neither RBI nor IBA was competent to interpret the provisions of the law (https://bit.ly/2KDFX72).

If indeed IBA moves a court of law, it will take years and the interest on the service tax claimed will balloon, making the burden heavier for banks, if they lose. The industry, I believe, is considering filing a writ petition with the Supreme Court of India for a faster resolution of the matter.

If banks are forced to pay up, the government will recover a substantial portion of the Rs2.2 trillion capital that it has committed to infuse in state-owned banks, but that will be moving money from one pocket to another. Profitable private banks may be able to pay off, but the five-year service tax payment will be the proverbial last straw that will break the public sector banking camel’s back.

While the banks will not be able to pass on the cost to their customers for free services in the past five years, from now on, banking will be an expensive affair. Banks will also probably stop waiving processing fees for home loans (which often they do now) and offering free credit cards. Overall, not a good news for Asia’s third largest economy, which is trying hard to bring more and more people under the banking fold.