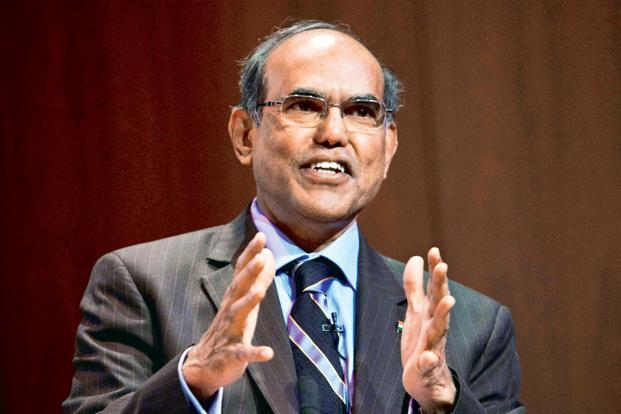

It is fairly certain that Tuesday’s monetary policy review, the last before the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor D. Subbarao steps down in September, is unlikely to have any action. The Indian central bank has reviewed its policy twice this month through measures to stamp out liquidity from the system and make money more expensive to protect a fast-depreciating local currency.

The market will, however, keenly watch RBI’s statement on Tuesday, and if bond dealers are expecting any hint of a rollback of the rupee protection measures, they will be probably disappointed. Subbarao may not commit to any time frame for reversing the liquidity-tightening measures even though the currency market is showing some signs of stability. While a stable rupee, over a period of time, will encourage the rollback of liquidity-tightening measures, RBI can only renew its monetary easing measures as and when retail inflation comes down. Wholesale inflation is well within its comfort zone, but retail inflation continues to remain high.

Till the April policy, Subbarao was balancing his priorities between injecting a growth impulse into a slowing economy and taming inflation. A depreciating local currency has opened up a new front for him.

Subbarao took up the assignment in the thick of a global credit crunch in September 2008, which followed the collapse of US investment bank Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. An ultra-loose monetary policy accompanied a series of fiscal sops to put back Asia’s third largest economy on the rails even as the credit crisis threatened to overshadow the Great Depression of 1930s in enormity. That predictably led to the rise in inflation and Subbarao had to tighten the monetary policy through a series of rate hikes. As a result of this, both wholesale inflation and so-called core inflation, or the non-food, non-oil manufacturing inflation, dropped, and when corporations started betting on a series of rate cuts to kick-start investments, the rupee played spoilsport. The currency’s depreciation started with the flight of capital and a worldwide sell-off in bonds and equities after US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke on 22 May first hinted at slowing bond buying under the so-called quantitative easing programme.

A weak rupee impacts both inflation and the fiscal deficit as the cost of import rises and the government needs to spend more on subsidies. In the past fortnight, Subbarao followed the textbook method of fighting currency depreciation. First, he capped banks’ borrowing at Rs.75,000 crore, or 1% of their deposits from RBI’s repurchase (repo) window along with a hike in the bank rate as well as the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate to 10.25%. This meant any bank wanting to borrow beyond Rs.75,000 crore from the repo window would need to pay three percentage points more than the repo rate (7.25%). RBI also announced a plan to sell bonds to soak up excess liquidity.

When these measures did not yield the desired results, RBI restricted banks’ access to money at its repo window further by capping it at 0.5% of deposits for individual banks. It also tweaked the norms on how much cash reserve ratio (CRR)—or the portion of bank deposits that banks need to keep with RBI—banks need to maintain daily.

These steps tightened liquidity, jacked up money market rates, and stabilized the rupee. The local currency, which hit its lifetime low of 61.21 a dollar on 8 July, closed at 59.04 on 26 July. The 10-year bond yield has risen at least half a percentage point. At the shorter end, the three-month treasury bill yield has risen by about 3.5 percentage points. Overnight call money rates are also above 10% now, from around 7% a week back.

Banks have been crying hoarse as they would need to book huge mark-to-market (MTM) losses because of sharp rise in bond yields. MTM is an accounting practice of valuing financial assets at their market value and not the cost at which they were acquired. The estimated MTM loss figures for the industry vary between Rs.15,000 crore and Rs.60,000 crore, and will dent banks’ profitability. For individual banks, the exact quantum of MTM loss will depend on the composition of their bond portfolio as they do not need to book losses on the so-called held-to-maturity (HTM) category of portfolio. The overall bond holding of the industry is a little more than 28% of deposits.

The liquidity-draining exercise serves two purposes. One, it increases the cost of speculation for those who are using rupee resources to punt on the currency. Two, the rise in rates encourages foreign funds to buy Indian debt papers. The combination of a lack of speculation in the currency market and foreign funds flow bolsters the local currency. These measures also theoretically encourage exporters to bring back export proceeds—dollars—as they feel that the rupee will not depreciate further and hence there is no incentive in delaying the process of bringing back dollars. Similarly, the importers will not rush to buy dollars as they feel the cost of buying dollars will not go up even if they do it later. So, it augments the supply of dollars and dents demand for the greenback.

Collateral damage

RBI’s measures have succeeded to some extent, but the banking system is suffering from collateral damage. Had the central bank allowed the rupee to depreciate further, the banks would have been saved, but corporations would have borne the brunt as many of them have not hedged their overseas borrowings. This, in turn, would have affected the banking system and the stressed corporations will eventually default in repaying bank loans. So, either way, the banking system has no escape from the fallout of a depreciating rupee.

It’s a bit tricky for RBI, too. On 30 January, 2010, after raising CRR by three-quarters of a percentage point, signalling the beginning of monetary tightening, Subbarao had said: “Getting out of an expansionary policy is incredibly more complex than getting in. It is like the chakravyuh in Mahabharata. You know how to get in, but it is very difficult and not many people know how to get out.” Indeed, he is finding himself in a chakravyuh now. For long, RBI has been following an accommodative monetary policy to keep the cost of government borrowing down even when inflation was high. It also allowed the rupee to appreciate despite a record-high current account deficit. Had it been slow in cutting rates and CRR and allowed the local currency to gradually depreciate against the dollar, it would have been a different story.