When Raghuram Govind Rajan came to India as the government’s chief economic adviser two years ago, everyone warned him about the bureaucracy. “People told me the bureaucracy here will be very difficult to deal with—very smart people but with very different agendas.”

Rajan, 51, hasn’t found much truth in that. “If you have paid attention elsewhere and if you are not completely naïve, there isn’t a whole lot that is surprising or different. It is slightly different here inasmuch as there isn’t often a sense of urgency. Things that need to be done yesterday are still not done, in some cases. But that’s not surprising.”

When he took over as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor on 4 September, he was handed a report by a committee he had headed in 2008 which recommended differentiated bank licences (where different kinds of banks do different things as opposed to the current crop of universal banks). Predecessor Duvvuri Subbarao had liberalized (branch licensing) right up till tier 2 cities but had then hit a roadblock. “So my initial effort was to pull all those things that were in the planning stage and say let’s finish. There’s no reason for things to season.”

Rajan even has a term for this style of policymaking. “One way to do things is to say let us think in theory, develop the best plan possible and then implement in one go. I call this the Brahminical way. But this may not work as at the implementation stage you will realize that some aspects were not considered. The alternative is, roll up the sleeves, don’t minimize the thinking phase, but do it quickly. I am trying to do that. There’s this Chinese phrase, ‘Cross the river by feeling the stones’. It’s basically step-by-step, but take that step, don’t theorize about how you’re going to cross the entire river, not knowing where the steps are… Take the first step and feel your way through the next step, be more practical about it.”

Extended honeymoon

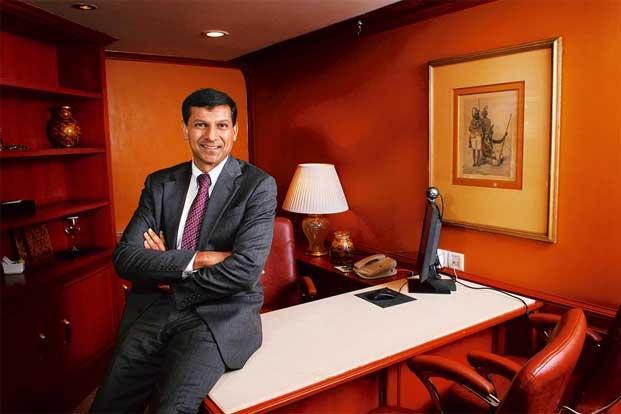

We’re having lunch in the RBI visitors’ room, adjacent to Rajan’s 18th-floor corner office in Mumbai’s Fort area. The menu features everything you could possibly think of, from green pea soup and stuffed pomfret to prawn balchao and badami murg—all from the RBI kitchen run by chef Brian Pais.

Rajan walks in a few minutes past 1pm. A warm handshake later, I ask him bluntly whether he offered to resign when the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance government took over in May. After all, he was appointed by the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. Rajan doesn’t seem annoyed but prefers not to answer this question, even off the record. “Of course, if I lost the confidence of the government at any point, I would go the next day,” he says curtly.

Was the governorship part of the arrangement when he took over as chief economic adviser? I ask him even before we sit down to lunch.

“There was no arrangement,” says Rajan.

We plough through all the food with the portraits of 16 of RBI’s 22 past governors (Subbarao is still not there though it has been a year since he stepped down) looking down at us.

Rajan had two conditions when I invited him for lunch: One, let’s meet at the RBI and two, no personal questions. He is a vegetarian, although he doesn’t mind eating eggs. So, the onus of eating all that meat and seafood is on me, but I find him keeping a close eye on my plate. “Are there too many bones? Would you care for a fresh plate?” he asks me while eating a chapati with Paneer Birbali.

In August last year, the UPA government announced the name of the next RBI governor a month before the position fell vacant and Rajan, then chief economic adviser, was sent to the RBI as an officer on special duty—something that had never happened in the RBI’s 79-year history.

It was a tough gig. Inflation had been high for years but what added to the problem was a record high current account deficit, a falling local currency against the greenback and the real threat of a ratings downgrade.

One year on, the rupee has stabilized, the current account deficit is manageable, Rajan is not shy of raising policy rates to fight inflation and, most importantly, the government is backing him to the hilt in his fight against inflation. He is under no pressure to cut interest rates to boost growth in Asia’s third largest economy.

Unbelievably, Rajan’s honeymoon with industry and people in general continues. What’s the secret? “Look at the Indian cricket team. They are gods, they can’t do any wrong, and then they come down to earth after they lose a few matches. I am waiting for something to happen to bring me down there, even though I can’t say I am looking forward to that. I see my job as a kind of a mission. I have to keep doing what I do. And take the decision without looking to who’s happy and who’s not,” he says.

Born in Bhopal in 1963, the third child of a police officer, Rajan’s rise in the world of economics has been meteoric. A gold medallist at both the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, and the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, he did a short stint at Tata Administrative Services as a management trainee before getting a doctorate in management from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management in the US.

In 1991, he joined the University of Chicago Booth School of Business as an assistant professor of finance and worked there till August 2003, when he was appointed chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In 2005, at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, at the annual central bankers’ conference, Rajan tore apart US Federal Reserve board chairman Alan Greenspan’s work and reputation. A 2009 Wall Street Journal report on his presentation says Rajan even argued that the banking system itself would be at risk and banks would lose confidence in one another. “The inter-bank market could freeze up, and one could well have a full-blown financial crisis.” Two years later, that’s exactly what happened.

Rajan still believes that financial reforms take “A Hundred Small Steps”, the title of a 2008 paper by a committee that he headed, where he spoke about inflation targeting and a floating exchange rate among other things. “Whatever you put in place, the success of that you will see in years down the line, especially in the financial sector, where things have to catch on…. There is a sense in India that we are uniquely different from the rest of the world. In some ways we are, but in many ways some of the issues we find here are similar to the issues you find anywhere else.”

Rajan plays squash or runs daily. In January, he participated in the Mumbai Half Marathon. When it comes to work though, he’s been more of a sprinter than a marathon man from the beginning. “We have stabilized the currency. We need to bring inflation under control and bring NPAs (non-performing assets) down—those two things are still ongoing. They will take time to fully get tackled. But at least we made a quick beginning. Going forward, it was also to show that we could put down the agenda for revitalizing the financial sector—banking, markets, inclusion. We are taking steps and we have to see how they play out. For example, the interest rate futures market in India is picking up in liquidity, but still at about Rs.1,500 crore a day, it’s relatively small. This has to grow. We need to have more players coming in. Let’s move and let’s keep fiddling (with) the structure to get it right,” he says.

Of course it’s not easy to work fast in an organization like the RBI. The central bank has been known to sit on things but rarely says no. “This is an organization with tremendous capabilities but it is also a bureaucracy, in the non-pejorative sense of the word. Sometimes the bureaucracy delays things in order to essentially say no without saying so. Especially in a country, where sometimes saying no is seen as a slap in the face, it’s better that the issue slowly dissipates over time rather than having to take a decision. Some policies that seem inordinately delayed should be seen in that light—perhaps there’s a fundamental disagreement over the policy, and therefore the best way to kill it without prompting a confrontation…,” he says.

Rajan agrees that people are always trying to see how far they can push the central bank to see their point of view. “Of course, there’s immense pressure on the RBI from different quarters—I can certainly attest to that—to relax on every front of our regulations and supervision. People asking you to relax on those fronts sometimes are trying to see how far they can push you. Of course, if the system gets into trouble, the RBI will bear the blame because it’s the stability regulator, but before that everybody will push you to be ‘flexible’. There will be pressure, but the appropriate response RBI may have found is dignified silence.”

Restructuring RBI

Meanwhile, work is on to modernize the behemoth. After all, it was set up in the 1930s, at a time when the world was reeling under the Great Depression, and since then its objectives have remained unchanged. “We are undertaking some internal reorganization of RBI’s structure and how it functions. There will be concerns, like any other reorganization, and we have to take the staff along with us. But the whole idea is to make it an organization which is fully capable of meeting the challenges of the 21st century. We need to figure out how to move towards specialization. Training and support is a second issue. We need good performance evaluation and once we evaluate weaknesses, we need to offer support in terms of skill building,” says Rajan.

The RBI board has already approved Rajan’s ambitious plan. He refutes the idea that he plans to import talent from outside. “In an organization that has grown as it has, it’s better to grow the internal talent than bring too many people from outside as they will be seen as competing for the existing jobs. You can bring people in if you are expanding, but you have to be very careful in doing it and do it in small doses only.”

Rajan declines the fresh fruits and ice cream and opts for coffee instead. It seems like the right time to ask him about commentators who have described him as India’s newest sex symbol (in Shobhaa De’s words, “The guy’s put ‘sex’ back into the limp Sensex”). Many of my female colleagues at Mint swoon over him and even those who don’t know the way to the RBI headquarters on Mint Road are keen to attend his press conferences.

Rajan, 6ft, 1 inch, blushes but soon recovers to say: “My wife Radhika teases me a lot about this. I worry that there is a real danger that you distract from the very important and sober task of policymaking. But that said, the value of having glamour introduced into some professions is that it attracts young people into that profession. If a boring economist can become glamorous, maybe economics is something worth pursuing.

“When I was young, I read about (John Maynard) Keynes. And I said what a glamorous guy, doing great policies, writing great books; wouldn’t that be a good thing to do? And what did he do? Economics. We look at people who catch our eye, and then we learn more about what they do and that helps attract us to the field. I think we need more economists, so in that sense I am not upset.”

It’s well past 2.15pm and I see him looking furtively at his watch. I ask him what he does when he is not writing monetary policy and not thinking about financial stability. “Squash in the evening or in the morning, depending on the day and depending on if I haven’t torn any muscles. Now my son is home (he is studying in the US), we play video games together. I talk to my daughter (who is also studying in the US); occasionally go out with my wife to visit friends. I love reading, and sometimes I write. I do write all my speeches. I like to run, if I can find the weather cooperating, I like to visit places, if we can go out to a new place for a board meeting, I try to look around. Eating out is a little difficult these days simply because people recognize… They don’t interrupt you but still I feel a little embarrassed, my son feels even more embarrassed.”

The liveried RBI waiter appears with a tray of paan, formally signalling the end of our meeting. I pick up two and without losing a moment shoot my last question to Rajan: He has achieved so much in such a short time. Even if he remains RBI governor for five years, he will be 55. What will he do after that?

“I like writing and thinking. What next is back to the future, go back to writing and thinking, with the idea that I have learnt a lot about India and will write more about it—what I think is going right and wrong. Not a ‘tell-all’ book but a thought-piece like my other books. But I have no fears about a life of quiet contemplation. Actually that’s my other side. I think my wife is perfectly happy staying quiet and going underground. And we have no desire to be in the limelight.”

He may not like this but I am sure limelight will always chase him.