On December 7, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) cancelled the licence of the Karad Janata Sahakari Bank Ltd in Maharashtra and barred it from conducting the business of ‘banking’ as it did not have adequate capital and earning prospects. On that day, the bank also went for liquidation.

This is the third such instance in 2020. Earlier this year, the banking regulator had cancelled the licences of two other co-operative banks — CKP Co-operative Bank Ltd, also in Maharashtra, and the Mapusa Urban Co-operative Bank of Goa Ltd — for similar reasons.

Cooperative banks have always been a sore area for the RBI, and this year has been no exception. But a couple of private sector banks have been a bigger nuisance. On November 17, Lakshmi Vilas Bank Ltd (LVB), which was placed under the so-called prompt corrective action framework a little over a year back and thus restrained from giving fresh loans, was put under a 30-day moratorium. Nine months before that, in the first week of March, a much larger Yes Bank Ltd had undergone a similar process because of steady deterioration in health.

In both the cases, the moratorium was lifted much ahead of the schedule, the depositors did not lose a rupee and the banks were rescued with electrifying speed – although through very different rescue operations. A bunch of banks, led by the nation’s largest lender, the State Bank of India, took over Yes Bank, while the Indian subsidiary of DBS Bank Ltd, Singapore, merged LVB with itself.

Indeed, tackling the Covid-19 pandemic was the biggest challenge for the Indian financial system in 2020, but episodes such as LVB and Yes Bank almost threatened the financial sector stability, at least in public perception. There have been other structural changes on the regulatory landscape through the year.

Three failures in cooperative banking only took the story of the multi-state Punjab and Maharashtra Coop Bank in 2019 forward. Cancellations of licences apart, the RBI has issued over a hundred directives to such banks this year, curbing their operations or extending the restrictions imposed earlier. Many cooperative banks, across geographies, are on the RBI radar and the scene is unlikely to change dramatically despite the amendment to the Banking Regulation Act this year, which has brought this tribe of banks under the RBI’s regulatory framework. Urban co-operative banks and multi-state co-operative banks – which have about 86 million depositors and a portfolio of close to Rs5 trillion deposits – are now under the RBI supervision, but the primary credit cooperative societies continue to remain outside the purview of the seven-decade-old Banking Regulation Act. Many of them, like the larger cooperative banks, are a cesspool of politics and misgovernance.

The rules of the game have this year been changed for another weak link in the financial system – the housing finance companies (HFCs). In October 2020, the RBI prescribed that housing finance must constitute 60 per cent of total assets of an HFC by March 2024. The revision followed RBI taking over as the regulator of mortgage lenders from National Housing Bank. The HFCs, now regulated as a category of non-banking financial companies, must stay liquid. A glide path has been charted out for the change in their business profile. Those who fail to rejig their business in accordance with the new norm run the risk of losing their registration.

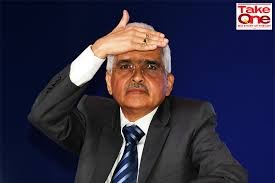

Of course all these developments are minor skirmishes compared with the war against the pandemic. One must say that as a general, RBI governor Shaktikanta Das has marshaled his resources rather well.

At least three RBI governors in the past three decades faced enormous challenges during their tenure as the country’s chief money, but Das’s task has been far more daunting. In November 1997, Bimal Jalan moved to the Mint Road in the thick of the East Asian crisis, which was driving the value of rupee down every day; D Subbarao saw iconic US investment bank Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc collapsing, plunging the world into an unprecedented financial crisis just nine days after he took over the office; and, in September 2013, Raghuram Rajan moved in when India’s current account deficit was at its historic high and the local currency was in a tailspin against the greenback.

Das’s predicament has been very different. While the government announced a Rs29.88 trillion three-package stimulant between May and November, it includes the RBI’s liquidity measures and roughly translates into a fiscal stimulus of just 2.3 per cent of the GDP — far lower than what most Covid-affected nations have been willing to spend. So, Das has to play the role of Titan Atlas in Greek mythology, bearing the weight of the economy on his shoulders albeit with a difference – the burden is not a punishment for him as it was for Atlas, by Zeus.

After two out-of-turn rate cuts, by 1.15 percentage points, in March and May, the RBI’s repo rate (at which commercial banks borrow from the central bank) is now at a historic low of 4 per cent. In a liquidity-flush situation, the reverse repo rate (at which banks park excess money with the central bank) becomes the de facto policy rate. By that yardstick, India’s policy rate is 3.35 per cent now.

Cutting rates is one of the many weapons in Das’s armoury in the fight against the pandemic. Through a series of conventional (such as cut in the banks’ cash reserve ratio) and unconventional instruments (targeted long-term repo operations, or TLTRO), the RBI has flooded the system with liquidity and repeatedly assured the market that it would do whatever it takes to bring back growth impulse in the economy. The abundance of liquidity is helping the record Rs22 trillion central and state government borrowing through without much noise.

For the borrowers, there has been a moratorium on loan repayment even as the bankers have seen allowed to restructure certain kinds of exposures to stymie growth in bad loans.

All these are leading to a recovery that is faster than what most analysts and the RBI itself had estimated. Bankers have been talking about near-normalcy in the collection of loan repayments and very few stressed borrowers approaching them for loan restructuring. It will take some time to know whether all these are for real or the banking system is just postponing the inevitable, but for now they give us hope for 2021.

One thing is for sure though: The unwinding of the expansionary policy measures could turn out to be a far bigger challenge for the RBI next year. More on this in my next week’s column.