Last week, at the Mint’s 10th Annual Banking Conclave in Mumbai, one question was common for both former Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor D. Subbarao and the current chiefs of large India banks: what do they expect from the union budget?

Subbarao wants the government to stick to the fiscal consolidation path but most bankers (not all) want India’s finance minister to focus on growth, even if that means a slightly expansionary budget. Chiefs of the three biggest state-owned banks also said they would like the budget to take note of the capital requirement of banks.

Most analysts say that the government will be able to stick to the target of a fiscal deficit of 3.5% of gross domestic product, or GDP, in the current fiscal year that ends in March and aim for at least 3.3% fiscal deficit for 2018. The government has been diligently lowering the fiscal deficit for seven years since 2012 when the deficit touched 5.9% of GDP.

Subbarao feels that even though there could be a slowdown in growth in the wake of the so-called demonetisation exercise, the government should adhere to the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act which seeks to institutionalize financial discipline.

The original objective of the Act was to bring down the fiscal deficit to 3% of the GDP by March 2008 but in the aftermath of the global meltdown, the Act was first postponed and later suspended in 2009. A committee headed by former revenue and expenditure secretary N.K. Singh to reconsider reinstating the provisions of the Act submitted its report on 23 January, a week before the presentation of the budget.

The report is not in the public domain but people familiar with its recommendations say the N.K. Singh Committee—whose members include RBI governor Urjit Patel and the chief economic adviser to the finance ministry Arvind Subramanian—is in favour of fiscal consolidation but not sacrificing growth.

While no one can question the importance of keeping the fiscal deficit low, the budget should also focus on reform in the banking industry. Many of the government-owned banks that have around 70% share of banking assets are laden with bad loans and need capital to stay afloat. Indeed, the banking system plays the most critical role in carrying out the government’s development agenda but precious little is being done for the banks.

But for them, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, the most ambitious financial inclusion programme ever undertaken in any part of the world, would not have been successful. Till 11 January, some 266.8 million new accounts have been opened and 210 million debit cards have been issued. One-fourth of such accounts still do not have any money in them but post-demonetization, the collective balance in such accounts has swelled to Rs69,000 crore. The banking industry also made sure that around Rs15 trillion worth of Rs1000 and Rs500 notes have come back to the system in 50 days in the biggest ever currency swap programme in the world.

In his address to the nation on 31 December, a day after the banks closed the currency swap window, respecting the “autonomy of the banks”, Prime Minister Narendra Modi appealed to them to move beyond their traditional priorities, and keep the poor, the lower middle class, and the middle class at the focus of their activities. He announced cheaper home loans for the poor, 30 million debit cards for farmers, doubling the amount of loan (taken from banks as well as non-banking finance companies) to be underwritten by the government and higher fund flow to the small industrial units, among other things. The budget may have many more such schemes for rural development and employment generation but we need a healthy banking system to implement such schemes.

The RBI’s December Financial Stability Report has pointed out that the gross non-performing loans of the Indian banking industry rose to 9.1% in September 2016 from 7.8% in March, pushing the overall stressed loans to 12.3% from 11.5% and it will rise further. While these reflect the health of the industry, the state of affairs in the public sector banks is far worse. Their stressed loans are at least 16%, more than three times than that of private banks. In fact, the report has said that the public sector banks may record the highest bad loans and lowest capital adequacy ratio, a measurement of capital against risk-weighted assets, among all banks. Has the government done anything meaningful to address these issues?

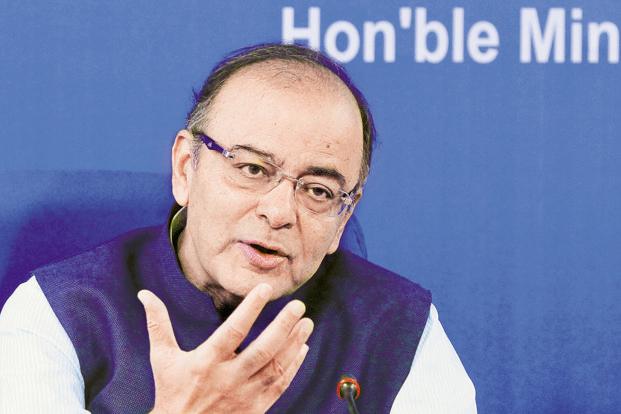

The government had held an offsite with the banking bosses, Gyan Sangam, in Pune, in January 2015. Addressing the bankers, Modi had said it was a “unique initiative” and “the first step towards catalyzing transformation”. In August 2015, finance minister Arun Jaitley announced the grand Indradhanush plan—the “solution to the problems” of the industry, which Modi explored in Gyan Sangam. It promised to tackle several critical issues, including appointments, capitalization, stress in the system, empowerment, accountability and governance reforms to revamp functioning of the government-owned banks.

Estimating the capital requirement between fiscal year 2015 and 2019 at around Rs1.8 trillion, assuming 12-15% growth in bank credit, the government has committed to pump in Rs70,000 crore in phases till 2019 when the new Basel norms kick in. It also feels that the public sector banks’ (PSBs) market valuations will improve significantly following governance reforms, tight bad loan management and risk controls, significant operating improvements and, of course, capital allocation in successive budgets.

Higher valuations, coupled with sale of non-core assets as well as improvement in performance would enable these banks to raise money from the market, the government had said.

It also issued a circular that said there would be no interference from the government and the banks would be encouraged to take their decisions independently, keeping the commercial interest of the organization in mind.

A government note describes the Indradhanush framework for transforming the PSBs as “the most comprehensive reform effort undertaken since banking nationalisation in 1970” adding, “Our PSBs are now ready to compete and flourish in a fast-evolving financial services landscape.” If indeed setting up of the Banks Board Bureau with a string of vague and ambiguous terms, splitting the top post in PSBs between chairman and managing director and CEO and appointing a few private sector bankers as heads of PSBs are meaningful reforms, then Indradhanush has done wonders.

Even though the credit growth has been far lower than what has been estimated, the banks would need higher capital as growing bad assets are eating into their capital but none has any idea what’s happening on that front. The banks are required to set aside money or provide for their bad assets and that erodes their capital.

As far as the Banks Board Bureau is concerned, I wonder whether even the members of the Bureau themselves know what they are expected to do.

Its mandate includes selection and appointment of managing director and CEOs as well as non-executive chairman of PSBs, helping banks develop a robust leadership succession plan for critical positions, advising the government on the formulation and enforcement of a code of conduct and ethics for bank executives, and helping banks develop business strategies and capital raising plan, among others.

Barring the top level appointments, all other assignments are vague and even here, the Bureau does not have the final say. One-fifth of Indian Overseas Bank’s loans have turned bad and it has recorded losses for six successive quarters till December (to the tune of Rs5,786.63 crore) but it doesn’t have either the chairman or a managing director and CEO for seven months since its last boss retired in June 2016. Apparently, the Bureau recommended the executive director of a PSB for this position and it was cleared by the vigilance authority—a necessary precondition for any top appointment in a PSB—but a division of the finance ministry shot it down. Clearly, there is a disconnect between the ministry and the Bureau.

The Bureau also recommended nine candidates for the posts of executive directors in various PSBs in September, but none of them has been appointed as yet. Moreover, it does not have the power to appoint the so-called non-official directors at boards of PSBs, many of whom are the root cause of mis-governance in banks.

The government’s plan to dilute ownership in IDBI Bank has also gone nowhere. Similarly, the employee stock option plan or ESOPs for PSBs remains a promise on paper so far.

In sum, barring a few cosmetic changes, nothing significant has been done to revive the public sector banks. I would love to see finance minister Arun Jaitley using this budget to move forward with a concrete reform agenda. Or, will genuine reform remain a rainbow (Indradhanush) for India’s public sector banks forever?