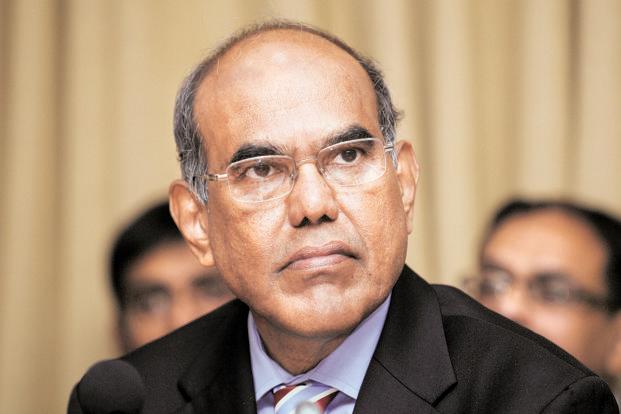

Mumbai: Hours after cutting the policy rate by a quarter percentage point to 7.25% in the annual monetary policy for fiscal 2014 on 3 May, the last of his tenure, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor D. Subbarao , in an interview with Mint , said: “I cannot say absolutely (there is) no space (for monetary easing in future). If we had to communicate (there is) absolutely no space, then we would have used the word ‘no’. We said ‘little’.”

The response was consistent with what he had said in March.

In the March mid-quarter policy review, after a quarter percentage point rate cut, Subbarao had said the headroom for monetary easing was “quite limited”.

The governor’s language has not changed despite the drop in wholesale inflation as well as core inflation. In February, wholesale inflation was 6.84% and non-food, non-oil, manufacturing inflation, or core inflation, was 3.79%. In March, wholesale inflation dropped to a 40-month low of 5.96% and core inflation to 3.48%, its lowest since February 2010. (To be sure, these are provisional figures and the final ones could be higher.) This, along with a sharp drop in crude and gold prices, encouraged the market to expect a relatively dovish statement from the RBI, if not a reduction in banks’ cash reserve ratio (CRR) to accompany the rate cut. But that did not happen. CRR is the portion of deposits that commercial banks need to keep with the central bank.

Subbarao, the inflation warrior, has stuck to his guns. Indeed, he cut the policy rate by a quarter percentage point to 7.25%—a level last seen in May 2011—but laced his action with a caution that there is little space for monetary easing. He even warned that if the situation warrants—meaning, if inflation and the current account deficit rise—there could be a reversal of the policy stance. That sent bond yields rising, the local currency slipping against the dollar, and equities, particularly bank stocks, falling.

Rate cut in June?

Subbarao’s hawkish tone may be aimed at tempering market expectations in Asia’s third largest economy, which is yet to see any growth momentum. As wholesale inflation is expected to drop further—the southward trend will continue until September—there could be two more rate cuts (by a quarter percentage point each) with the first of these on 17 June in the first mid-quarterly policy of fiscal 2014. RBI will also need to cut CRR, now at 4%, to infuse liquidity into the system. Theoretically, it can be pared to any level, even zero.

The daily average cash deficit in the system in April was around Rs.87,000 crore; it crossed Rs.90,000 crore in the first few days of May. However, the core cash deficit is lower as the government continues to keep its surplus cash with RBI. Since this money is not a part of the system, it adds to the cash deficit. Once the government starts spending, the cash deficit will come down in the short run but, ultimately, it will rise because of record government borrowing and force RBI to cut CRR. For the time being, it can buy bonds from banks through its so-called open market operations (OMOs) to ease the pressure on liquidity. In fact, it kicked off OMOs for fiscal 2014 on 3 May, immediately after the policy announcement, with a Rs.10,000 crore bond-buying plan. Last year, it bought Rs.1.55 trillion bonds through OMOs.

The government will borrow Rs.5.79 trillion this year to bridge its estimated 4.8% fiscal deficit. After the redemption of old bonds, the net borrowing will be Rs.4.84 trillion. So far, it has borrowed Rs.60,000 crore. To accommodate such a massive borrowing programme, RBI may have to cut CRR by half a percentage point in phases during the year, which will release around Rs.35,000 crore (on the basis of the current deposit portfolio of banks), and another Rs.1.65 trillion can be infused through OMOs.

RBI can also cut the banks’ statutory liquidity ratio (SLR), or the floor for banks’ compulsory bond buying, to release money that can be used to give loans to borrowers. This can be pared to 22% from the 23% that it is now, although most banks have much higher bond holdings anyway. In fiscal 2013, RBI had cut the SLR floor by 1 percentage point.

Little space vs no space

In the Mint interview, Subbarao said, “We said ‘little space’ for monetary easing to mean that unless the growth-inflation scenario is more optimistic than we believe it to be, the space for further monetary easing is not there. What it means is that if the current account deficit improves more than we expect or if the inflation situation moderates faster than we expect, or if the upside risks become more benign, space might open up for further easing…”

The current account deficit (CAD) touched a record high of 6.7% in the third quarter of fiscal 2013, taking the average in the first nine months of 2012-13 to 5.4%. CAD is expected to drop in the fourth quarter, but it could still be around 5.1% for the fiscal. Even though wholesale price inflation has been dropping, March consumer price or retail inflation was 10.4% and it may remain at an elevated level because of a reduction in fuel subsidies. RBI follows the wholesale price inflation more closely than retail inflation.

C. Rangarajan, chairman, Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, echoed Subbarao’s sentiment when he told reporters on 3 May, after the policy was unveiled: “If inflation tends to move in the direction of…5%, I would think there would be greater space… I do not think you should read from the sentence that there is no possibility…”

A not-too-happy P. Chidambaram, India’s finance minister, said, “Let’s accept what has been done today and let us see what the future holds… If inflation were to fall further, it would provide room for further monetary easing.”

One may argue that the 3 May rate cut is a wasted effort by RBI as it will not translate into any lowering in loan rates by banks. “There’s not much scope for a cut in lending rate. There is nothing to transmit. Even a 1 basis point (cut) is much too high,” said Pratip Chaudhuri, chairman of State Bank of India, the nation’s largest lender.

A policy rate cut by RBI brings down the rate at which commercial banks borrow from the central bank, but banks don’t use this to give loans. The money for loans comes from deposits and banks cannot cut their loan rates as long as deposit rates remain high. RBI cut its policy rate by one percentage point and CRR by 75 basis points (bps) in fiscal 2013, but the banks have on average reduced their loan rates by 36 bps. This is because they have not been able to cut their deposit rates by more than 11 bps on average. One basis point is one-hundredth of a percentage point.

With inflation declining, banks may be able to pare their deposit rates and, consequently, loan rates will come down; but that will take months. Besides, some Indian banks enjoy high net interest margins (NIMs), the difference between the interest rates they charge for loans and pay on deposits. They possibly need a relatively higher NIM to take care of the cost of transactions, overheads and the wage bill. They can bring down their loan rates only if they can increase efficiency. Very high government borrowings also soak up a large part of their resources, leaving little for private borrowers. Since banks earn less than 8% from investments in government bonds, they need to charge higher rates to their borrowers who end up subsidizing government borrowing.

No sign of growth impulse

The May policy rate cut is the fourth time since April 2012 that the Indian central bank has lowered its key policy rate, adding up to a total of 125 bps. Yet, any firm indication of a growth impulse in the world’s 10th largest economy is still absent.

This is because the slump in growth is due more to the absence of fresh investment and governance issues rather than the cost of funds. The average factory output growth in the first 11 months of the fiscal—between April and February—was 0.9%, the lowest since 2009. And both the HSBC Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) and Services PMI dropped to 50.7 and 51, respectively, the lowest in about one-and-a-half years. Car sales declined in fiscal 2013 for the first time in a decade and there was no change in the trend in April. Air passenger traffic rose only marginally—1.59%—in March after falling for 10 successive months till February.

RBI expects wholesale inflation to be range-bound around 5.5% during the current fiscal, even though the ideal level for the year-end is 5%, and it has projected growth in gross domestic product at 5.7%, lower than the government’s forecast of 6.1-6.7%, the World Bank’s estimate of 6.1%, and the Prime Minister’s economic advisory council’s projection of 6.4%. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) growth projection for the calendar year ending December 2013 is 5.7%.

“The Reserve Bank is clearly more pessimistic than the government is,” Planning Commission deputy chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia commented after RBI released its policy. “I think that the government forecast as of now is feasible.”

The central bank put the blame squarely on the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government for not doing enough to make the environment conducive for a revival in growth.

“Recent monetary policy action, by itself, cannot revive growth,” RBI said. “It needs to be supplemented by efforts towards easing the supply bottlenecks, improving governance and stepping up public investment, alongside continuing commitment to fiscal consolidation.”

The central bank highlighted its concern over prices.

“With upside risks to inflation still significant in the near term in view of sectoral demand-supply imbalances, ongoing correction in administered prices and pressures stemming from MSP (minimum support price) increases, monetary policy cannot afford to lower its guard against the possibility of resurgence of inflation pressures,” RBI said.

photo

Even though the central bank doesn’t set itself an inflation target, RBI governor Subbarao has positioned himself as a lone inflation warrior. While many feel that he should follow a relatively easier monetary policy to push growth, the governor does not want to let his guard down on inflation.

In March, while delivering the fifth I.G. Patel memorial lecture at the London School of Economics, he had said, “Monetary policy is inevitably the first line of defence to guard against inflation getting generalized through unhinged inflation expectations… The Reserve Bank has to ensure inflation is brought down to the threshold level and is maintained there.” Maintaining that the India growth story is still credible, he had said, “we need to do the right things” to get back on to a high-growth trajectory and called for “vigorous and purposeful structural and governance reforms” to achieve this.

In May 2011, speaking on the sidelines of a Bank for International Settlements (BIS) meeting, Subbarao had said he would maintain his anti-inflationary stance even if that meant sacrificing growth in the short term. “In the short term, inflation is a problem for growth in India and we need to pin down inflation first in order for growth in the medium term to be sustainable, even if it meant sacrificing growth in the short term.” At that time, wholesale price inflation was 9.58% and core inflation was 7.34%. Both have come down sharply since then, but Subbarao has not budged an inch from his stated stance.

This is possibly his way of keeping the pressure on the government to be fiscally responsible. He has takers for his stance within RBI and its technical advisory committee that advises the bank on the monetary policy. Wholesale Price Index (WPI) based inflation may slow to 5% or even lower by September when Subbarao steps down as RBI governor after a five-year stint. Would this signify a victory for Subbarao? That depends on what has contributed more to it—RBI’s monetary policy or the fall in global commodity prices—but lower inflation (and a manageable CAD) will definitely give the central bank a handle to cut rates. A drop in the cost of money, a normal monsoon, lower oil and gold prices and a government determined to improve the investment climate could well revive the India story.