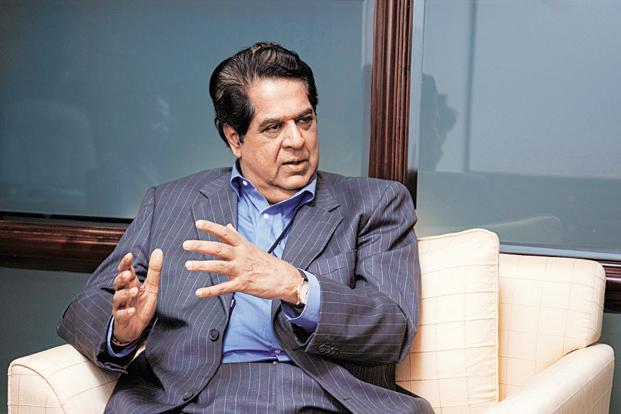

Mumbai: K.V. Kamath , chairman of India’s largest private sector bank ICICI Bank Ltd, does not care much about the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) move to hike the key repurchase rate. In the mid-1990s, when he took over as chief of ICICI, the project finance institution that eventually merged with its commercial banking arm, it borrowed at 16% and lent at 19% and there were still takers for money.

Interest rates now are much lower; what is hurting projects are delays in securing government clearances. “The investment cycle is broken and there’s very little that interest rate adjustments can do to fix it,” Kamath said in an interview on Tuesday. “What is required is clearing the logjam, in terms of policy.” He also said steps taken by the cabinet committee on investment, formed to speed up projects, are producing results.

Action on the interest rate front, according to Kamath, has very little consequence at this point, but if liquidity continues to be tight, funding of some of these projects in the pipeline could be a challenge. Edited excerpts:

Do you see corporations being enthusiastic in investing in new projects?

Corporate India was in a fairly dejected mood for the last, say, 18 months. With the cabinet committee on investment in place, I am seeing some signs of positive mindset. I hope that momentum continues and I believe that government can always act.

RBI has hiked the repurchase rate. It seems that rates can only go up from now on.

Nobody can fault the monetary policy authorities for saying that inflation is the biggest challenge. Indeed, there are multiple challenges—inflation; a very volatile currency market, which is willy-nilly going to impact a whole lot of structural issues, and you have twin deficits.

RBI governor Raghuram Rajan is a very seasoned economist. He is also a pragmatist. So he would have seen all the challenges and, among them, he probably picked what he thought should be addressed first. He might have felt that we need to correct the short end of the curve first and get rates down there so that the curve looks proper.

At the same time, he is getting the long end of the curve up, which may provide some stability to the exchange rate.

It’s clear the rates will not go down. They can only rise.

Yes, it’s clear that in the long end, rates will not go down at this point. But I won’t say that they will go up because I think the next thing that probably will be done is to examine the root cause of inflation.

Should inflation control be the primary mandate for RBI?

Inflation control has always been a mandate and, certainly, it has to be. But, at the same time, I don’t think central bankers have said growth is not a concern at all. I think growth is also something that they are concerned with. Actually, you cannot separate these two.

The question is: Why is it that you have not been able to get a handle on inflation for the last almost 36-40 months? You need to figure out that and then you administer the right medicine. Surprisingly, interest rate as a medicine did not work.

How do you see the impact of the latest RBI move on the investment scenario?

I would want to de-link what happened in the monetary policy from the investment scene.

Seventeen years back, when I took over as managing director of ICICI, people were borrowing at 19% and 20%. In fact, we were borrowing at 16% and lending long-term money at 19%. Yet, we had takers. We might have created an uncompetitive industry as a consequence.

This time around, interest rates are nowhere at that level. I don’t think interest rates are hurting projects in corporate India. What is hurting is clearances, which dents the ability to implement a project. That is resulting in piled-up debt.

The investment cycle is broken and there’s very little at this time that interest rate adjustments can do to fix it. What is required is clearing the logjam, in terms of policy. There, the steps taken by the government, particularly the cabinet committee on investment, are bearing fruits.

The government is trying to fix the investment cycle and get at least a few projects of substantial investment to take off so that they can kick-start economic progress. The actions on the interest rate front really have very little consequence. As you go along, if liquidity continues to be tight, funding of some of these investments could be a challenge. We are not facing that as of now.

What about individual consumers?

Yes, the place where interest rate is significant and will cause pain is the consumer segment. At least for the last 12 years, we have had an economy which was driven by both investment engine as well as consumption engine working in tandem. At this point, the investment engine, particularly the infrastructure investment engine, is stressed. The consumption engine is not broken; it is still ticking. I would sense that if interest rates rise, we could get into a stressed situation on that engine and we should avoid that.

Why are public sector banks accumulating more bad debt, compared with their counterparts in the private sector?

Everybody has seen projects from a given basket. By and large, that basket is made up of big-ticket infrastructure projects. I would think the primary cause for distress is those infrastructure projects which have been stuck. The choice of projects is causing some of these problems to get accentuated in a particular set of banks.

It is just I think you ended up with some wrong selection of projects. I don’t think it is a wrong credit decision; it is the projects that were selected had these problems, which we did not anticipate.

Is the worst over for bad debts or could they still go up?

It’s a difficult call. When I see the cabinet committee is pushing things, then I think the projects will again start moving and that will alleviate a whole lot of issues. If they don’t, you will see a whole lot of problems. We need to see the basic areas where they are stuck… It is easy to de-bottleneck and get going… Otherwise, there could be more pain.

Banks’ cost of funds is going up chasing quality customers, but they are not in a position to claim high rates. Do you think Indian banks will live with a lower net interest margin (NIM)?

The high NIMs of Indian banks were warranted by very high intermediation cost. Our ticket sizes of loans were very small and the risk in the system was higher and to allow more for risks, you needed higher NIM.

Now, your cost of funding is increasing. You are not able to squeeze out the cost. There is another thing which is actually impacting the NIM. I don’t see anybody articulating it clearly. Some of us, project finance lenders, have seen it in the past—what I call NIM contraction due to non-accrual of interest rate on non-performing assets (NPAs). When the top-line goes off, your NIM immediately contracts.

I think a lot of banks are seeing it for the first time. Historically, when you had cash credit, this never happened as banks used to debit interest to the cash credit account. This always happened… Only a few of us have faced several cycles of non-accruals because of NPA movement. This is the reason for NIM contraction and I think this cannot be corrected.

To correct it, you need to lend at a very rapid pace, which is not happening. Or you need to get interest rates down at a rapid rate, that is also not happening.

I think for a large number of banks, NIMs will continue to be under pressure primarily because of the NPA impact.

How do the banks tackle this? By seeking higher fee income?

I have seen ultimately the only thing that works is growth. Fee income is not a magic wand—growth is the magic wand. Your book expands; you earn healthy income, and you book a healthy NIM. A bank can never insulate itself from the overall economic environment. You can try to build safeguards; you can build margins; you can build cushions, but never fully insulate yourself from the overall economic environment.

Is the worst over for the economy?

On the economic front, I clearly think we are at the bottom. If you look at the constituents of what is driving growth, there are a few which are still robust, and I don’t see any signs that they will be challenged. For example, rural India—the entire rural economy is much larger than agriculture—is in a very robust stage and is growing. If we, as a nation, rely on that as a significant part of momentum provider, we will see economic growth kicking in. It has already kicked in.

Also, the services sector has come up the highs of 11-12% growth, but probably is still growing at 6-7%. That’s probably 60% of the economy. So you have got a strong engine of growth.

Manufacturing is growing at a marginal rate and infrastructure is not growing at all. You can then look at the sectors which are hurting.

The sectors which are humming will not let you go below 5-5.5%. But to get back to 8%, you need the other sectors to fire on all cylinders.

Your take on the food for all law.

This is not a cliché. I don’t think anybody can oppose the food for all law. We need to see how to make it happen without the leakages; without the ills that we know we have; if we can administer it in a way that will be easy to absorb. I don’t think we can say we are a democracy without ensuring this basic need.

You always advocated scale in banking. Now that RBI is readying to give new bank licences, how many banks should be given the nod to set up shops?

The Financial Sector Reforms Committee envisaged a much larger number of banks appropriately populated across the country. I would think the needs of inclusion is the model one needs to look at. This should mean that bank licences are on tap and takes a completely different path. Of course, there is one caveat—you need to simultaneously ensure that your supervisory structures are in place. Otherwise you will have consequences.

The policymakers will decide on what will be the path—just a few licences, or licence on tap, or fully opening up the sector… All I am saying is that you have a report, prepared just a few years back, which has espoused that there should be many banks and we should follow that.

We need to see things particularly from the financial inclusion standpoint. I think from this standpoint, we need to look at all different models. If you look at the US, there’s a large number of cooperative and credit unions running. We will understand it as we go along. My own gut is that it will be much more open than what we have been thinking.

Are you disappointed with the government for inaction?

I think it is not a question of inaction by the government. Till we started halting on a few issues, which can be broadly called governance issues, the economy was ticking nicely. I honestly cannot say that if you put a brake, because of the governance issues, it’s a wrong thing. You did a right thing braking for governance issues, like for environment issues. However, you should have a resolution process which is much faster. Frankly, that’s what the cabinet committee on investment is now trying to do.

Why couldn’t it have been done two years back? That is where we lost momentum in the economy.

Now that elections are round the corner, would you look for a new government?

I never talked on politics. I believe that every government can deliver.

What does the government need to do to change the investment climate?

First, you must remove the roadblocks which are holding up investments in infrastructure. Till we get that right, whatever we do, we will not get growth beyond 5-6%.

Second, you need to bring stability on the deficit front. You need to get stability on the exchange front. You need to get your liquidity equations right and the lending rate right. I am not saying at what stage we are at, but, I think, each one of these needs to be addressed honestly.

I would say 5%, or in that range, growth will happen in any case. If we need to get to 8-9% growth, we need to get to look at all these. We may not be able to handle them immediately, but there should be a sequence to do that.