Last year, a chief manager of a public-sector bank (PSB) in Rajasthan was served a notice a day before he was to retire. The charge related to an alleged fraud in financing a real-estate project in 2022. Following a departmental enquiry which had lasted close to two years, quite a few bankers at different levels in this PSB – directly or indirectly related with the process of sanction and disbursement of the loan – came under vigilance scrutiny.

For the chief manager, this was the first chargesheet in his unblemished 35-year career. As he had no time left before retirement to face long departmental inquiry proceedings and defend himself, the banker accepted the charges. If he had not, he would have been denied several retirement benefits, including pension, until the conclusion of inquiry, which could have taken a few years. On the last day of his career, he was punished with a six-scale pay reduction: Six annual increments (plus dearness allowance on the basic pay) were slashed for calculating his pension.

In another instance, a chief general manager of a PSB was linked to a large loan that turned bad. Following this, a vigilance inquiry was proposed. This found a mention in his CV when he was appearing for an interview for promotion to the executive director (ED) position.

The gentleman was eventually exonerated from the charges, but he missed several opportunities to become an ED, as the reference to the vigilance inquiry was held against him at every interview. After a long wait, he became an ED, but not a managing director, as time ran out for him to become eligible for the corner room.

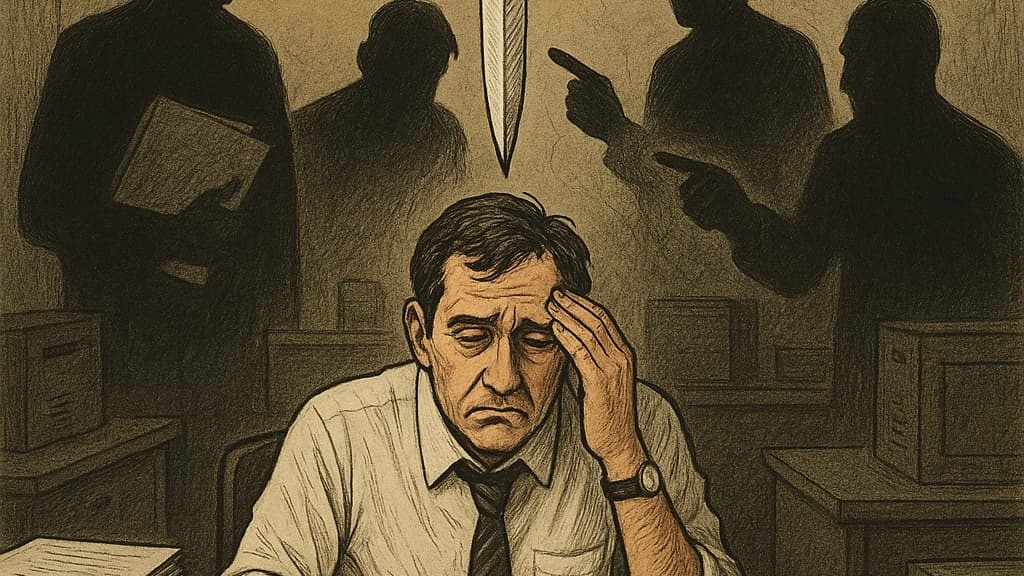

For India’s public-sector bankers, vigilance enquiry is the proverbial “Sword of Damocles”. The phrase originates from a Greek legend about Damocles, a courtier of King Dionysius-I of Syracuse.

An avid admirer of the king’s opulent lifestyle, Damocles was once invited by the king to a banquet. There, he was made to sit under a sword, suspended by a single hair. The king’s intention was to demonstrate to Damocles the constant fear and anxiety that even the most privileged lives must endure. Even a seemingly minor event could trigger a catastrophic outcome, creating a sense of constant unease and potential doom.

This is what the decision makers and their associates feel every day at every level at PSBs. Of course, unlike the king, they don’t enjoy opulence.

They deal with public money and make decisions which can go wrong at times, leading to financial loss for a bank. The key question a bank needs to ask: Is this a case of commercial decision going wrong? Or, is there a mala fide – carried out in bad faith or with the intent to deceive?

A vigilance inquiry is meant to find the answer. But, in many cases, such an inquiry is a never-ending process, killing the morale and efficiency of the bankers concerned. So, many choose not to take any decision, to escape the Damocles’ Sword.

The departmental inquiries are conducted behind closed doors, and the burden of proof does not lie with the presenting officer who plays the role of prosecution lawyer. The mention of a few lapses and primary documentary evidence are more than enough to implicate the accused banker directly or indirectly.

The inquiry officer, part of the management and typically senior to the accused by one level, is an independent observer who submits his findings to the disciplinary authority which appoints him. The disciplinary authority plays the role of a judge who has the power to make decisions, based on the gravity of charges. Most bankers in private say the entire process in some banks fits the proceedings of a kangaroo court – the rule of natural justice is hardly followed, and the decisions are predetermined.

Going by the vigilance manual, the following things can trigger an inquiry:

# Demanding or accepting bribes.

# Obtaining valuable items from institutions with which they have official dealings.

# Owning assets disproportionate to one’s income.

# Gross and repeated negligence in duty.

# Irresponsible decision-making and blatant violations of systems and procedures.

# Cases of misappropriation, forgery, and cheating

# Recklessness in opening of accounts.

# Allowing frequent overdrafts in accounts.

# Falsification of records.

# And, submission of false TA/DA bills.

If a rising trend of bad loans is seen in accounts sanctioned by a branch manager who has lending powers, he could be subjected to a vigilance investigation. There is no fixed quantum regarding the amount of bad loans or the number of accounts turning bad.

The rulebook gives three months for the preliminary investigation. There is no specified time limit for seeking the so-called first-stage advice. Once the disciplinary authority and the chief vigilance officer (CVO) find a case is fit for probe, the first-stage advice is sent to the Chief Vigilance Commission (CVC).

Appointed by the Government of India in consultation with the CVC, the CVO, a bridge between the bank and the CVC and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), reports to the managing director of a bank. Typically, the executive is appointed from outside the bank to ensure impartiality and independence.

After receiving the first-stage advice, a bank initiates the process of issuing a chargesheet and departmental inquiry. The time taken for such an inquiry should not exceed three months and the entire process is expected to be completed within 15 months. However, these timelines are not always adhered to.

If any banker is aggrieved by the punishment imposed by the disciplinary authority, an appeal can be filed within 45 days of receiving the order. Usually, the appellate authority is an official one stage above the disciplinary authority in terms of seniority. If dissatisfied with the appellate authority’s decision, one can even approach the court. Bankers can also seek the court’s intervention for timely disposal of cases.

Last month, in AM Kulshrestha vs Union Bank of India case, the Supreme Court quashed the proceedings and ordered all retiral benefits to be granted to the affected officer. There are many such court orders where departmental proceedings are found to be not in sync with the guidelines. However, the courts usually do not interfere in departmental proceedings, unless there is material proof of violation of process.

Incidentally, the process and quantum of punishment for similar kinds of mistakes vary from bank to bank. I am aware of one case involving a general manager where the departmental inquiry was completed in a day and the charges were disproved. This was to ensure that he did not miss his promotion, the interview for which was slated the next week. Also, there have been instances where the allegation was against a group of officers but one of them got acquitted while investigation continued for others. Probably, it all depends on how connected you are.

For the record, between 2011 and 2015, at least 3,100 PSB officials were dismissed, and 5,600 were demoted due to vigilance-related actions. This translates into approximately three dismissals and six demotions every two days.

The latest available information about such cases relates to the 2023 calendar year. In that year, the CVC received 2,661 complaints (including 554 carried forward from 2022). Of these, 1995 were disposed of and 706 remained pending.

Going by the CVC annual report of 2023, 1,508 officers were punished in 2019. This number stood at 2,652 in 2020, and 2,476 in 2021. While 1,987 officers were punished in 2022 and 1,509 received punishments in 2023.

Of course, all these cases did not pertain to PSBs alone. For instance, while State Bank of India imposed penalties in 175 cases, the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs did so in 131, the Railway Board in 121, Union Bank of India in 56, and Bank of India in 46.

Indeed, the word “vigilance” is a dreaded term for PSB employees and there are instances where this fear is misused by the higher authorities to tame their subordinate officials.

This fear always deters PSB executives from making decisions – the fewer the decisions, the less the chance of falling into trouble. On the other hand, there is no reward for every correct decision taken. In the absence of this fear, the employees of private-sector banks move more aggressively, make business decisions collectively, and go bargain hunting. No wonder then that PSBs are losing their market shares.

The CVC has been emphasising the need for timely resolution of vigilance cases. Last month, it issued a circular asking officers to watch out for “reckless decisions”, stressing that commercial risk-taking was part of business and not every loss caused to a government organisation – financial or otherwise – needed to be probed.

A recent media report also mentions that a working group within PSBs is busy finalising guidelines to standardise operating procedure for any disciplinary action against employees. Let’s hope once this is in place, PSB employees will not find the Damocles’ sword hanging on their heads anymore.

The writer, Consulting Editor with Business Standard, is an author and Senior Adviser to Jana Small Finance Bank Ltd.

His latest book: Roller Coaster: An Affair with Banking.

To read his previous columns, log on to www.bankerstrust.in.

X: @TamalBandy